CSB PRAXAIR FIRE SUMMARY

Union Carbide a.k.a. Praxair

Praxair officials and their lawyers claimed that they have an "outstanding safety record"

A BRIEF PRAXAIRIAN HISTORY

In the marketing community, a "BRAND" name means everything in business. When the drunkin sailor of the Exxon Valdez ran his oil tanker upon a reef, the vessel (and company) could no longer be recognized as a trustworthy "BRAND".

In effect, the ship was renamed the

"SEA RIVER MEDITERRANEAN".

On the night of December 2 1984 (drunkin sailor)

CEO Warren M. Anderson's chemical plant in Bhopal, India experienced catastrophic plant failure and has killed to date over 15,000 people. On June 30 1992, to distance itself from this tragedy, the gas division was spun off to Union Carbide Corporation's stockholders. The "Ship" was renamed

"PRAXAIR"

OUTSTANDING SAFETY RECORD?

In 1898 the Union Carbide Company was created in Virginia to manufacture calcium carbide for acetylene lighting.

1930. Several hundred (700) Union Carbide workers died of acute silica poisoning while constructing a tunnel for hydroelectric power for Union Carbide near Hawk's Nest, West Virginia. Almost 400 lawsuits resulted in an out-of-court settlement of $130,000, after the victims' attorneys received secret payments to take no further legal action.

1950s-1960s. Mercury used for the separation of lithium-6 at Oak Ridge. A third of the world's mercury was brought to Oak Ridge. Some 2.4 million pounds of mercury are unaccounted for; while most is probably underneath buildings, 475,000 pounds leaked into a creek, and 30,000 pounds are believed to have leaked into the air. In 1955, almost half of workers tested had mercury in their urine at levels above those considered safe.

1973. Three employees killed at the Penuelas, Puerto Rico complex.

1973. Benzene gas leak at the Penuelas, Puerto Rico complex killed an employee.

1973. Employee at Institute, West Virginia killed by propane fumes.

1975. India granted Union Carbide a license to manufacture pesticides. Union Carbide Corporation built a plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, with Union Carbide owning 51 percent and private Indian companies the other 49 percent.

1975 February 10. An explosion at Union Carbide's Antwerp, Belgium polyethylene plant killed six employees. The plant was later sold to BP Chemicals.

1980 July. The U.S. Departments of Labor and Health & Human Services reported excessively high brain cancer rates at seven petrochemical plants. The second-highest rate was at Union Carbide's Texas City facility, where 18 workers had died of brain cancer.

1980 December. The Environmental Quality Board fined Union Carbide $550,000 for air pollution violations dating back to 1972 at its Yabucoa, Puerto Rico graphite electrode plant. See also the 1981 entry.

1981. Fire at the graphite electrode plant at Yabucoa, Puerto Rico.

1981. Union Carbide fined $50,000 for spilling 25,600 gallons of propylene oxide into the Kanawha River in 1978-1980.

1981 December. Newsday article on Union Carbide in Indonesia reported that more than half its Indonesian employees suffered from kidney disease due to exposure to mercury, that mercury levels in an Indonesian factory's well water were twenty times higher than levels considered acceptable in the U.S, and that surrounding rice fields and groundwater were also contaminated.

1982 May. Union Carbide inspection team indicated that the plant at Bhopal, India was unsafe.

1982 July. Hydrogen chloride leaked from a tank car at Union Carbide's Massey yard at South Charleston, West Virgina; several hundred residents were evacuated, a some were treated at the hospital.

1982 December 11. Tank containing acrolein exploded at the Taft, Louisiana plant; windows a mile and a half from the plant were blown out, and 17,000 people were evacuated

1983. An excess of cancer deaths is reported at Union Carbide's Seadrift, Texas plant. Workers exposed to polyethylene showed a seven-fold greater risk of lymphoma than the general public.

1984. West Virginia agencies fine Union Carbide $105,000 for hazardous waste violations.

1984 September 11. An internal Union Carbide memo warned of a "runaway reaction that could cause a catastrophic failure of the storage tanks holding the poisonous [MIC] gas" at the Institute, West Virginia plant. The memo was released in January 1985 by U.S. Representative Henry Waxman (D-CA), Chairman of the House Health and the Environment Subcommittee.

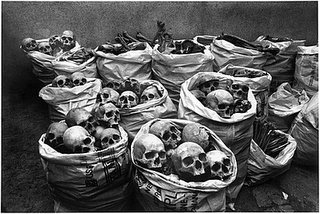

1984 December 2-3. Bhopal, India disaster killed thousands of people.

1984 CORPORATE STATEMENT ON BHOPAL: Company statements in its 1984 Annual Report included the following: "Bhopal was a shocking tragedy, but Union Carbide was well served by our quick and compassionate response, and by the way the situation was managed. We moved swiftly to provide emergency relief while concentrating management of the crisis among a small group of executives, so that unaffected businesses could proceed with their normal routines. Many were shocked that the accident had happened to Union Carbide, a company with an excellent safety record. Expressions of support for Carbide poured in from customers, suppliers, and friends around the world. Carbide was also sustained by the performance of our employees, who never faltered throughout the December crisis." "Numerous lawsuits have been brought... alleging, among other things, personal injuries or wrongful death from exposure to a release of gas... Some of these actions are purported class actions in which plaintiffs claim to represent large numbers of claimants alleged to have been killed or injured as a result of such exposure..."

In its 1984 Form 10-K (written in early 1985), the only mention of Bhopal was the following statement: "In part because of the accident in Bhopal, India, chemical companies, including Union Carbide, have had difficulty renewing their public liability insurance for the same coverage that had been in effect. In March 1985 Union Carbide renewed its personal injury and property damage insurance and now has substantially less of such insurance with broader exclusions and a substantially larger deductible than in 1984. Union Carbide is continuing to seek additional coverage."

1985. CORPORATE STATEMENT ON BHOPAL: "A settlement for $350 million has been proposed for the lawsuits seeking recovery for personal injuries, death, property damages and economic losses from the release of gas at Union Carbide India Limited's Bhopal, India plant in December 1984... The tentative settlement agreement is supported by the U.S. attorneys for the individual plaintiffs, but is subject to the approval of Judge John Keenan and of the Corporation's Board of Directors, and in addition, the Union of India must either agree to the settlement or a portion of the settlement must be reasonably identified and allocated for the Union of India's claims for its expenses from the release. The Corporation does not intend to conclude a settlement unless all claims arising out of the Bhopal gas release can be resolved with finality or provided for in the settlement process."

1985 March 1. The U.S. EPA filed a civil administrative complaint against Union Carbide under TSCA Section 8(e), seeking a civil penalty of $3.9 million for delayed reporting of skin cancer tests involving diethyl sulfate. The tests, which had been conducted at the Carnegie Mellon Institute of Research in 1976-1978, showed a high rate of skin cancer in mice treated with the chemical; Union Carbide did not notify the EPA until September 1983.

1985 March. 5,700 pounds of acetone and mesityl oxide leaked from a Union Carbide distillation column at its plant in South Charleston, West Virginia; dozens of area residents became ill after breathing the fumes.

1985 June. The U.S. EPA fined six corporations (Union Carbide, BASF Wyandotte, Ciba-Geigy, BASF Systems, Dow Corning, and B.F. Goodrich's Tremco subsidiary) more than $6.9 million dollars for failing to notify the EPA before manufacturing new chemicals; the names and uses of the chemicals were withheld by the EPA because the manufacturers claimed that was confidential business information protected by law. Union Carbide was fined $212,500 for producing a new chemical at its Sisterville, West Virginia plant.

1985 August 11. The Institute, West Virginia facility leaked methylene chloride and aldicarb oxime, chemicals used to manufacture the pesticide Temik; six workers were injured, and more than a hundred residents were sent to the hospital. Thirty people filed two lawsuits seeking $88 million in damages, but hundreds of people marched in support of the company. OSHA proposed fines of $32,100 for endangering workers, though later agreed to having Union Carbide pay $4,400 if it bought an accident simulator for training workers. Union Carbide spent $5 million to improve safety systems, but two more leaks occurred in February 1990. See also the January 23,

1985 November. Union Carbide charged that employee sabotage caused the disaster at Bhopal, India.

1986. Severance agreement between Union Carbide and former chairman Warren Anderson.

1986. The mayor of La Mesa, California asked Union Carbide to relocate its arsine-phosphine-ethylene oxide production facility. An attempt to locate it in Washougal, Washington failed. Amidst citizen protest in 1988-1989, the arsine-phosphine facility was relocated outside Kingman, Arizona. The plants were later transferred to Praxair, and one of them was sold to Allied Signal.

1986 April. The U.S. OSHA, after a September 1985 inspection of five of 18 plant units at Institute, West Virginia, alleged 221 violations of 55 health and safety laws, and proposed $1.4 million in fines. OSHA classified 72 of the 221 violations "serious," where there is substantial probability of death or substantial physical harm. OSHA had earlier given the Institute plant a "clean bill of health" after Union Carbide spent $5 million in safety repairs after the disaster at Bhopal.

1986 September. The Indian government filed Bhopal suit against Union Carbide, seeking $3 billion.

1987. BHOPAL: "... [M]anagement believes that adequate provisions have been made for probable losses with respect [to litigation]... The Corporation is vigorously defending the pending litigation... The Union of India alleged in [the November 17, 1986] proceeding [in Bhopal district court] that damages and losses arising from the Bhopal gas emission exceed $3 billion, which the Corporation strongly denies... The Corporation has appealed to the High Court in Jabalpur to set the order aside [for $270 million in interim compensation, of $15,400 for each death and $7,700 for each case of total disability]. The Corporation maintains that interim compensation for personal injuries cannot be allowed when the evidence as to liability is in dispute and the claimants' right to compensation has not been established. Given the Corporation's numerous defenses and the evidence that the tragedy was caused by employee sabotage, liability is in dispute... The Corporation believes that the [homicide] charges [against former Union Carbide chairman Warren Anderson] are without merit, and that Mr. Anderson, UCE [Union Carbide Eastern] and the Corporation are not subject to the jurisdiction of the courts of India in respect to criminal charges."

1987 July 24. Union Carbide Corporation agreed to pay $408,500 to settle 556 alleged health and safety regulations violations at its Institute and South Charleston, West Virginia plants; OSHA had originally proposed $1.4 million in fines for 462 willful violations.

1988 April. Indian court upheld order for Union Carbide to pay $190 million in interim relief to Bhopal victims.

1988 August 13. Fire and explosion of 4,300 pounds of ethylene oxide at Institute, West Virginia; tetranaphthalene was spilled into the Kanawha River, killing 3,000 fish.

1988 November. Bhopal district court issues arrest warrant for former Union Carbide chairman Warren Anderson after he failed to respond to a summons. See also 1991 and April 1994 entries

1989 BHOPAL: In February, the Supreme Court of India ordered a full and final Bhopal settlement of $470 million, and dismissed charges against Warren Anderson (the charges were revived in 1991). UCC&P and Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) paid the $470 million in a "final settlement of all civil claims." "Our goal from the beginning has been to get fair compensation to the victims as rapidly as possible." The Indian government, and the victims, contested the settlement.

UNION CARBIDE CORPORATION STATEMENT ON BHOPAL: "On February 14, 1989, the Supreme Court of India ordered a $470 million final settlement of all litigation with respect to the December 3, 1984 methyl isocyanate gas release at the Union Carbide India Limited ("UCIL") plant at Bhopal, India. The Corporation is a 50.9% shareholder of UCIL. The Union of India and Union Carbide Corporation accepted the Court's order. The Court stated that its order was just, equitable and reasonable based on the facts and circumstances of the case, including the pleadings, the data placed before the Court, the proceedings in the litigation in the United States, the settlement offers and counter-offers made by the parties, the complex issues if law and fact, the enormity of human suffering and the pressing urgency to provide immediate and substantial relief to the victims. The Court also quashed all criminal proceedings related to the gas release. Although the civil suit was filed by the Union of India against the Corporation alone, on February 15, 1989 the Supreme Court of India made UCIL party to the suit. The Court directed that the Corporation pay $425 million of the settlement and that UCIL pay the Rupee equivalent of $45 million. The $5 million payment previously made by the Corporation to the Red Cross at the suggestion of U.S. Judge John F. Keenan was credited to the Corporation, leaving a balance due of $420 million. The Court specified that the $470 million total be paid by March 23, 1989 to the Union of India for the benefit of all the victims of the gas release under the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act. "Effective upon full payment of the settlement, the Court discharged the previous undertaking of the Corporation in the District Court at Bhopal to maintain unencumbered assets having a fair market value of $3 billion. The Supreme Court proceedings also provide that the accused in the criminal proceedings are deemed acquitted. On February 24, 1989, the Corporation and UCIL delivered their respective payments to the Supreme Court of India, which payments were accepted by the Court." [On February 24, 1989, Union Carbide paid $420 million, and UCIL paid $45 million; "the payment was funded through proceeds from drawdowns of existing standby credit facilities. It is anticipated that these borrowings will be reduced during 1989 by application of insurance proceeds as well as internally generated funds."] "Various applications have been filed in the Supreme Court of India to set aside the settlement. The Corporation believes that those applications are without merit. At the time the settlement occurred, all of the suits that were brought in the United States with respect to the gas release had been dismissed. except a civil suit in the state court in Connecticut. The settlement will be placed before the Connecticut court. Also, plaintiffs in a civil suit in the state court in Texas that was dismissed have attempted to appeal the dismissal. If the appellate process proceeds, the settlement will be placed before the appellate court."

1989 April. Shareholders at Union Carbide's annual meeting rejected a plan to increase compensation to victims of the Bhopal gas leak.

1989 December. U.S. EPA conditionally proposed a civil penalty of $325,000 jointly against Union Carbide Corporation and Rhone-Poulenc Ag Company for violations of the Clean Water Act at the Institute, West Virginia facility.

1989 December 22. Supreme Court of India upheld the Bhopal Act, under which India represented the victims.

1990. BHOPAL: Union Carbide recorded "a charge of $58 million, representing litigation accruals principally related to resolution of the Bhopal litigation."

1990. Federal appeals court rejected a challenge by Union Carbide and the Chemical Manufacturers Association to overrule EPA regulations from 1989 on hazardous waste landfill liners and leak detection systems.

1990 January 12. The administration of the government of India announced it would support the victims' petitions to set aside the Bhopal settlement. See also the 1991 Bhopal entry for the rejection of these petitions.

1990 February. Union Carbide's Institute, West Virginia facility leaked methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas, injuring seven workers, and muriatic acid, after which 15,000 residents were ordered to remain indoors. See also the January 23, 1985, February 1985, and August 1985 entries.

1990 August. The Mexican environmental agency SEDUE took action against Union Carbide's Kemet subsidiary and six other companies for illegally dumping hazardous waste from the Parqu Industrial de Norte maquiladora at Matamoros, Mexico, near Brownsville, Texas.

1991. BHOPAL: In January, the Indian government again said the $470 million Bhopal settlement was inadequate, and said it would support the victims' petitions challenging it. By February, Union Carbide had collected $200 million from its insurance companies to cover Bhopal claims. In October, the Supreme Court of India rejected the victims petitions, upheld $470 million settlement, and lifted the company's immunity from criminal prosecution. A Bhopal court then revived culpable homicide charges against former chairman Warren Anderson (a warrant for him was originally issued in November 1988) and eight other Union Carbide officials. UCC&P and UCIL, at the request of the Supreme Court of India, announced that they would provide the government of India with up to $16 million for a hospital to be built in Bhopal, but by May 1992, with Anderson still not appearing in court, the government ordered the confiscation of Union Carbide Corporation's 50.9 percent share in Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL).

1991 March 12. An explosion at Union Carbide's No. 1 ethylene oxide and derivative production unit Seadrift plant near Port Lavaca, Texas killed John Resendez, a contract worker, and injured 26 others. The plant shutdown cost Union Carbide $50 million in net income. In September, the U.S. OSHA proposed a fine of $2,803,500 for 112 willful violations of health and safety regulations; $1.5 million was eventually paid. In March 1992, Union Carbide agreed to pay $3.2 million to the widow and two children of Resendez.

NOTE: The life of one American $3.2m. The life of an Indian? $600.00

1991 December 31. Chemical tank explosion killed an employee at South Charleston, West Virginia plant. An asbestos contractor reported the loss of asbestos in the explosion. Union Carbide was subsequently fined $151,000 for 23 health and safety violations.

1992. Union Carbide rejected a shareholder resolution for the corporation to sign the CERES (Valdez) Principles of environmental conduct. A similar resolution was rejected in 1993.

1992 March. Indian court orders extradition of retired Union Carbide chairman Warren Anderson.

1992 June 30. The Praxair industrial gases subsidiary was spun off to Union Carbide Corporation's stockholders after the Internal Revenue Service ruled that the split would be tax-free. "Union Carbide is now engaged almost exclusively in the chemicals and plastics business."

1993. For the second year, Union Carbide rejected a shareholder resolution calling for the corporation to sign the CERES (Valdez) Principles of environmental conduct. The corporation also rejected another resolution calling for it to disclose information on the risks of, and its procedures for, toxic chemical accidents.

1994 April 5. The Free Press reported that India's Central Bureau of Investigation had taken steps to have former Union Carbide chairman Warren Anderson extradited to India for his failure to appear in court in connection with the 1984 Bhopal disaster. See also November 1988 and 1991 entries.

1999 November. Lawsuit Seeks Compensation For 1984 Disaster Victims. A federal lawsuit filed Nov. 15 is seeking unspecified damages from Union Carbide Corp. for the "world's worst" industrial accident that killed at least 7,000 people in Bhopal, India, in 1984. The class-action suit accuses the company, which owned 50.9 percent of the plant, of "unlawful, reckless and depraved indifference to human life." The suit says the company and its former CEO, Warren Anderson, failed to comply with court orders in the United States and India after the accident. Union Carbide paid $470 million in a 1989 out-of-court settlement that gave company executives immunity from prosecution, but India's supreme court later struck down the immunity clause while letting the settlement stand. Many victims and their relatives are still waiting for compensation. Union Carbide accepted "moral responsibility" for the disaster but blamed a "disgruntled" employee (Greenwire, Nov. 18, 1999, citing Larry Neumeister, AP/New Jersey online, Nov. 16, 1999).

March 2000. Former Union Carbide Official Avoids Summons "A top executive at Union Carbide Corp. during the 1984 chemical disaster at Bhopal, India, has apparently gone into seclusion to avoid a summons to appear in a Manhattan federal court for civil proceedings against him and the company. Warren M. Anderson, who was the company's chairman, has vacated his last known address in Florida and Union Carbide officials have declined to help track him down, said Kenneth F. McCallion, the lawyer who initiated the civil case. Union Carbide says the settlement it reached with the Indian government in 1989 exempts it and Anderson from further proceedings. Union Carbide spokesman Sean Clancy: "Based on that settlement, we see no reason to encourage any disturbance of Mr. Anderson, who retired as chairman 12 years ago." But the Indian Supreme Court and a federal judge have ruled that the company must "submit to the jurisdiction of the courts of India." The company and Anderson, in absentia, are facing criminal charges in India. And a lawsuit filed in New York charges Union Carbide and Anderson with violating international law." (Greenwire, March 6, 2000, citing Chris Hedges, New York Times, March 5).

chronology found at

http://www.endgame.org/carbide-history.html

BACK TO INDIA

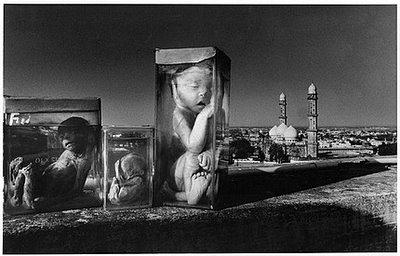

In 1996 Praxair (re)enters India. "Praxair" supplies India's steel, chemical, metal fabrication, medical, food, and other industries with oxygen, nitrogen, argon, hydrogen, helium and carbon dioxide through cryogenic air separation plants and other methods.

Local authorities in Bhopal filed criminal charges against both UCC its former CEO Warren M. Anderson in 1991-2. Anderson was charged with “culpable homicide (manslaughter),” facing a prison term of at least 10 years. He failed to appear, and is still considered an “absconder” by the Bhopal District Court and the Supreme Court of India.

However, despite the existence of a US-India extradition treaty, the Indian Government has failed to pursue a request for Anderson’s extradition vigorously.

The 82-year old Anderson, who is still subject to an Indian arrest warrant, has a very nice home with an unlisted number in Bridgehampton, New York, and another in Vero Beach, Florida.

(James S. Henry, SubmergingMarkets™, 2004)

mailto:inspectorprax@juno.com was an employee @ the Liquid Carbonic Co. when it was taken in a hostile take over by Praxair.

FAIR USE NOTICE

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of corruption, environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. visit praxair watch For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. PRAXAIR WATCH

From African Americans to East Indians, Union Carbides regard for minorities is unchanged.

The power of "PR" Burying the Hawk's Nest Disaster

It's recognized as America's deadliest industrial accident, but no one knows how many workers died from the dust they inhaled drilling a three-mile tunnel through what has been described as a mountain of "almost pure silica" near Hawks Nest, West Virginia, in the early 1930's.

What is known is hundreds of migrant and mostly poor workers, at the direction and full knowledge of Union Carbide, were sent with no safety protection to work every day in conditions the company knew would cause painful death. The result - within a year workers began dying of silicosis - a disease that normally takes 20 to 30 years to contract - at rates too high to imagine.

In a chapter of their recently released book, "Trust Us, We're Experts," Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber describe the deplorable conditions at Hawks Nest and how industry implemented a public relations campaign that not only improved the industry's image but all but removed the disaster at Hawks Nest from the country's collective memory.

Rampton and Stauber write, "The road that led from the workers' homes to the work site became known as the 'death march.' On their way home, the workers would be covered in white rock dust, giving them a deathlike appearance. Many of them were disturbingly thin, sick, coughing and bleeding. 'I can remember seeing the men, and you couldn't tell a black man from a white man. They were just covered in white dust.' Recalled a woman who lived near the Hawk's Nest tunnel."

Death tolls from what has become known as

"the Hawks Nest Incident" have ranged from a few hundred to over two thousand workers killed. At the time, so disgusted were Americans at learning of the incident, Congress was pressed into mounting a full inquiry into the disaster. The investigation showed Union Carbide not only knew of the health hazard and willfully disregarded safety equipment and techniques to guard against exposure, but even went so far as to instruct company doctors to withhold from their patients the source and extent of their condition.

The investigation also revealed that thousands of workers across the country were developing silicosis as a result of their working conditions.

All of the attention brought on by the tragedy heightened interest in work conditions and silicosis. Magazines and scientific journals went to work publishing articles on the "dusty trades" while the Department of Labor declared "war" on silicosis.

This was good news for workers.

However, it was not so good news for business.

Days following the end of the Congressional investigation into Hawks Nest, fearing impending lawsuits, industry executives formed the

Air Hygiene Foundation (AHF) to "give everyone concerned an undistorted picture of the subject." The "subject" in this case being silicosis.

Using leading scientist and public officials, the AHF raised doubts about the diagnosis and effect of the disease. The industry began implementing voluntary reform measures designed to improve their heartless image as much as to reduce the debilitating, often deadly effects of the disease.

So successful was AHF at beating back silicosis, that by 1940, AHF claimed 225 member companies, including some of the most toxic of the day, such as American Smelting and Refining, United States Steel, PPG industries, and of course, Union Carbide.

AHF over the years has widened its reach to cover a growing assortment of occupational health areas, changing its name in the process, first to the Industrial Hygiene Foundation and then to the Industrial Health Foundation.

As for the legacy of the Hawk's Nest disaster, Rampton and Stauber offer the following observation:"In the mid-1930s, silicosis was regarded as the 'king of occupational diseases,' as well known and notorious as asbestos would become in the 1990s. Thanks in large measure to the work of AHF, however, it began to fade from the headlines by the end of the decade" It's disappearance from the headlines is arguably a bigger scandal than the cover-up at Hawk's Nest, because the disease itself has not been eliminated, even though its cause is well understood and avoidable." © 2006 Wisconsin Laborers District Council

Hawk's Nest: A Novel by John Skidmore

by John Skidmore

The building of a tunnel at Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, beginning in 1930 has been called the worst industrial disaster in American history: more died there than in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and the Sunshine and Farminton mine disasters combined. When West Virginia native Hubert Skidmore tried to tell the real story in his 1941 novel, Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation apparently convinced publisher Doubleday, Doran & Co. to pull the book from publication after only a few hundred copies had appeared. This is the riveting tale of starving men and women making their way from all over the Depression-era United States to the hope and promise of jobs and a new life. What they find is "tunnelitis" or silicosis, a disease that killed over seven hundred workers, a large number of them African Americans, virtually all of them poor.